History of the Elwood McGuire House

The Elwood McGuire House

On June 7th, 1900, Elwood McGuire bought a double lot on East Main Street, just east of Nineteenth Street. He commissioned local architect/builder Stephen O. Yates to design and build the house. The house was built in 1901 and transfer books show an improvement value of $3,600. The house is a two-story brick structure designed in the Free Classic Style. Later changes to the property include the construction of a detached garage, and extending the side porch into a Porte Cochere and constructing a sunroom above it. The dates of these changes are unknown. McGuire continued to live in the house until at least 1912. Newspaper accounts report him spending considerable time in Colorado Spring, Colorado. He sold the house to Thomas and Kathryn Jenkins in 1918 and retired to Colorado Springs.

There are two possible motives for why McGuire chooses East Main Street to construct his ostentatious home. First, during this time many wealthy people were moving out of the original city core and looking for large highly visible lots to show off their wealth. Residing along the main road allowed them to display their wealth and class to everyone. Secondly, the proximity to Glen Miller Park was a huge bonus. Glen Miller Park began with the purchase of a tract of land by John F. Miller in 1880. Over the next five years, he developed this park and in 1885, the City of Richmond bought this for public use. This well-kept park had a large pond, trails, landscaping, and electric lighting. This follows a very Victorian love of romanticized nature and the City Beautiful Movement which was taking hold across the country at the turn of the century.

Historic research compiled by Clint Kelly, Graduate Assistant - Historic Preservation, Ball State University.

On June 7th, 1900, Elwood McGuire bought a double lot on East Main Street, just east of Nineteenth Street. He commissioned local architect/builder Stephen O. Yates to design and build the house. The house was built in 1901 and transfer books show an improvement value of $3,600. The house is a two-story brick structure designed in the Free Classic Style. Later changes to the property include the construction of a detached garage, and extending the side porch into a Porte Cochere and constructing a sunroom above it. The dates of these changes are unknown. McGuire continued to live in the house until at least 1912. Newspaper accounts report him spending considerable time in Colorado Spring, Colorado. He sold the house to Thomas and Kathryn Jenkins in 1918 and retired to Colorado Springs.

There are two possible motives for why McGuire chooses East Main Street to construct his ostentatious home. First, during this time many wealthy people were moving out of the original city core and looking for large highly visible lots to show off their wealth. Residing along the main road allowed them to display their wealth and class to everyone. Secondly, the proximity to Glen Miller Park was a huge bonus. Glen Miller Park began with the purchase of a tract of land by John F. Miller in 1880. Over the next five years, he developed this park and in 1885, the City of Richmond bought this for public use. This well-kept park had a large pond, trails, landscaping, and electric lighting. This follows a very Victorian love of romanticized nature and the City Beautiful Movement which was taking hold across the country at the turn of the century.

Historic research compiled by Clint Kelly, Graduate Assistant - Historic Preservation, Ball State University.

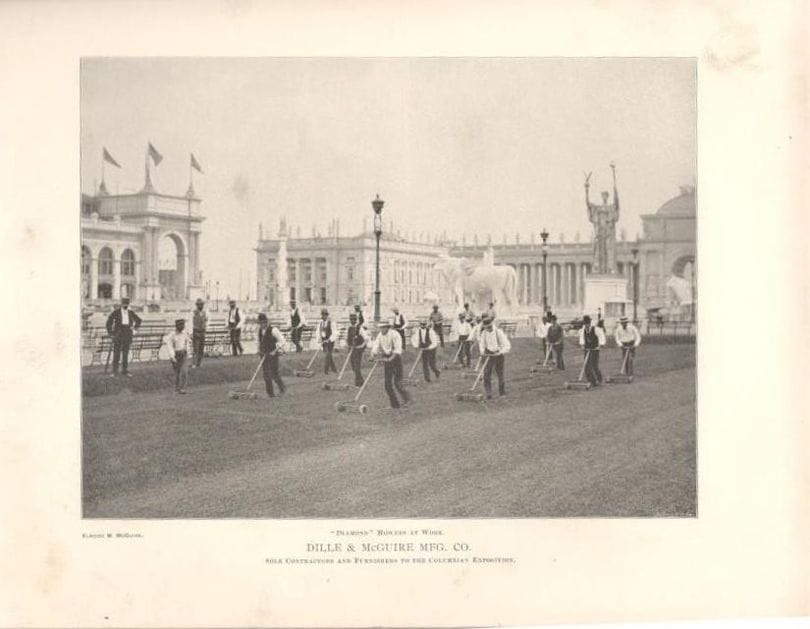

Dille & McGuire mowing the lawns at the 1893 Worlds Columbian Exposition

Elwood Whitney McGuire was born in Eaton, Ohio on May 5th, 1853 to Ezekiel and Eliza (Hunt) McGuire. He was educated in the public schools, graduating from Lawrenceburg High School in Lawrenceburg, IN and attended Whitewater College in Centerville, IN. In addition to his academic education, he was apprenticed to the Quaker City Machine Works as a wood pattern maker for three years. After this apprenticeship, he traveled for a year and settled in Richmond to practice his vocation.

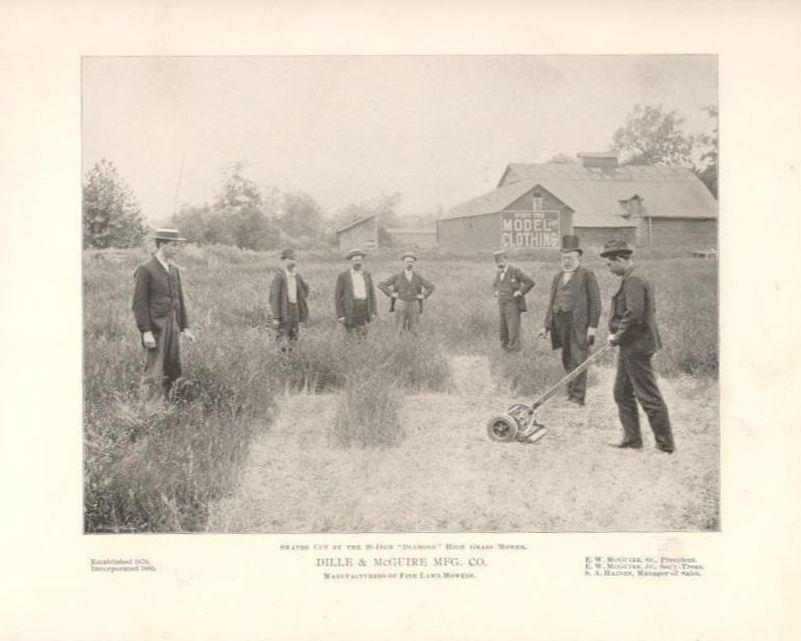

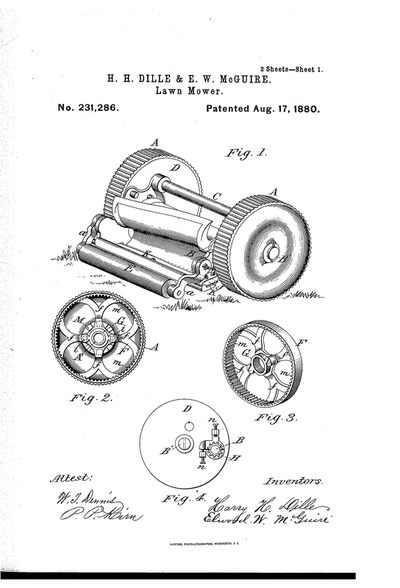

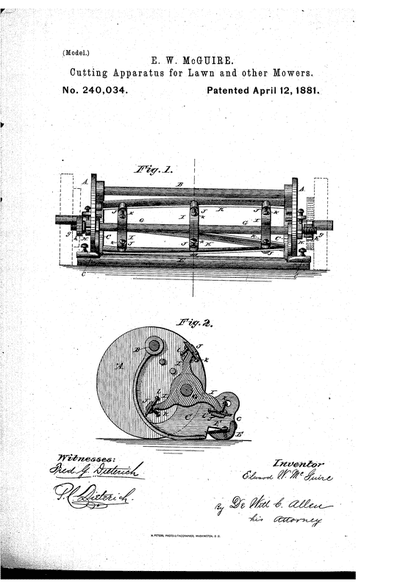

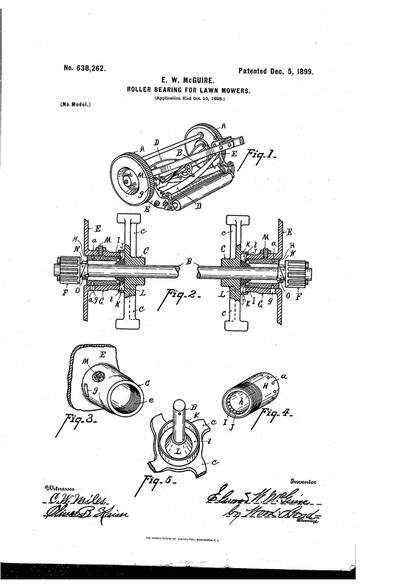

In 1870, he formed a partnership with Henry H. Dillie, a local machinist. Their shop was located on Fort. Wayne Avenue and was called “Dillie & McGuire, Machine Shop.” While Dillie had his tools of the trade, McGuire invested several hundred dollars to acquire new machinery. Eventually, their workload became heavy enough forcing them to hire workers. The partners made a habit of paying all debts and salaries on Saturdays and splitting what was left. Around 1874, a farmer came in to have blades on a fodder cutting machine sharpened. During conversations, this customer produced an advertisement for the Farebee mower. The mowers he saw were heavy, awkward, and expensive. He had an idea to make the mower lighter and easier to use. The new lighter design was patented and began to be sold for $12 for a mower with a twelve-inch cut. The new price point was cheap enough that this mower was available to more customers.

The business became very profitable and they outgrew their machine shop and needed new quarters. They moved to a factory on 13th Street adjacent to the railroad tracks. They originally named their new business “Richmond Lawn Mower Company,” but changed it to the “Dillie & McGuire Manufacturing Company” after several lawsuits were filed by the Eastern Manufactures’ Association. The partners continued with this business until 1890 when the McGuire bought Dillie’s interest in the business. Dillie’s name was retained in the company name. When McGuire gained sole control of the business, it was in deep debt. McGuire’s leadership pulled the company out of debt and became very profitable.

Historic research compiled by Clint Kelly, Graduate Assistant, Historic Preservation - Ball State University.

In 1870, he formed a partnership with Henry H. Dillie, a local machinist. Their shop was located on Fort. Wayne Avenue and was called “Dillie & McGuire, Machine Shop.” While Dillie had his tools of the trade, McGuire invested several hundred dollars to acquire new machinery. Eventually, their workload became heavy enough forcing them to hire workers. The partners made a habit of paying all debts and salaries on Saturdays and splitting what was left. Around 1874, a farmer came in to have blades on a fodder cutting machine sharpened. During conversations, this customer produced an advertisement for the Farebee mower. The mowers he saw were heavy, awkward, and expensive. He had an idea to make the mower lighter and easier to use. The new lighter design was patented and began to be sold for $12 for a mower with a twelve-inch cut. The new price point was cheap enough that this mower was available to more customers.

The business became very profitable and they outgrew their machine shop and needed new quarters. They moved to a factory on 13th Street adjacent to the railroad tracks. They originally named their new business “Richmond Lawn Mower Company,” but changed it to the “Dillie & McGuire Manufacturing Company” after several lawsuits were filed by the Eastern Manufactures’ Association. The partners continued with this business until 1890 when the McGuire bought Dillie’s interest in the business. Dillie’s name was retained in the company name. When McGuire gained sole control of the business, it was in deep debt. McGuire’s leadership pulled the company out of debt and became very profitable.

Historic research compiled by Clint Kelly, Graduate Assistant, Historic Preservation - Ball State University.